Banned

Banned

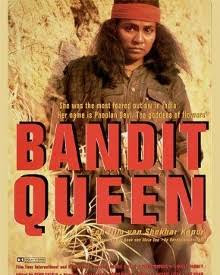

Bandit Queen

The film Bandit Queen released in 1994 is based on the biography of Phoolan Devi ,'a dakku' in the inhabitated forests of Chambal by 'Mala Sen' a London based Indian author.

The film story revolves around the struggle, exploitation and injustice faced by Phoolan Devi throughout her life .The story depicts the harsh and cruel face of the Indian society with beating around the bush ;it refers to the devastation due to caste system in Hinduism,sexual abuses, child marriages,blind faith leading to ill customary practices. These include indulgence in monetary greed,sexual assaults, domestic violence,male dominance in society etc ...so this was ought to be banned .The story shows us how an innocent mind was converted into a ruthless bandit .Phoolan in her early childhood was married to an elderly man, who abused and tortured her. After cursing her destiny young Phoolan figured out that she should just flee from there, but again she was raped by the high class order Thakurs who dominated the lands. Depressed Phoolan ultimately decided to evolve and revolt through violence after she was raped by the police officers, and the assassination of her lover added to her plight..She becomes a Bandit in order to seek revenge and surrenders herself to policemen after the huge bloody massacre .

The controversy on the movie began when the real life Phoolan Devi wasn't happy with the film and was denied to the premiere of the movie .Although Phoolan Devi is a heroine in the film, she fiercely disputed its accuracy and fought to get it banned in India. She even threatened to immolate herself outside a theater if the film were not withdrawn.The producer said publicly that Devi was invited to the premiere (only for cast and close people) at Cannes but she wasn't able to get the passport to Cannes (location of the premiere) .Eventually, she withdrew her objections after the producer paid her £40,000. Author-activist Arundhati Roy in her film review entitled, "The Great Indian Rape Trick", questioned the right to "re stage the rape of a living woman without her permission", and charged Shekhar Kapoor of exploiting Phoolan Devi and misrepresenting both her life and its meaning.

Yet this wasn't the reason for the ban.

The makers submitted the film to the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) on 17 August 1994. The examining committee comprising an examining officer and four members of the advisory panel saw it, raised objections, and referred it to the revising committee.The revising committee headed by a chairman, nine members of the censor board and advisory panel recommended an A certificate, subject to cuts and modifications. The revising committee, clamping down heavily on cuss words, rape sequences and frontal nudity, “added more than 100 cuts”, says Bedi -the producer.The story would not have been traced to the viewers without the highlight scenes which depicted the glory and aim of the movie.Hence they declined the orders and they applied to the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT), the next recourse in the censorship process, challenging the revising committee’s decision in the scene after a long battle the FCAT won. And created a benchmark for the censorship commandments. The revising committee had demanded that 70% of the scene of Phoolan Devi torturing her husband be cut. The FCAT believed it was a “powerful scene demonstrating Devi’s pent-up anger, emotions, and revulsion whose reduction would negate its impact”. The revising committee had asked for another scene, where Phoolan Devi is paraded naked in the village, to be cut heavily. The FCAT asserted that it was “an integral part of the storyone that intended to create revulsion in the minds of the average audience towards the tormentors and oppressors of women. To delete or even to reduce these climactic visuals,and would be a sacrilege.”The FCAT’s unanimous decision overruled the revising committee’s orders, and gave the film an A certificate.Even after the release another written petition to the police by a Gujjar community member due to the plot says that it demeans them, thus the movie was banned again and this time taken to supreme court for justice.Where the movie was passed after a lot of delegations.In the midst of the whole chaos a part of India rose up for the movie which unlike other movies showed up an agenda which the nation needs to have a thought at.The most shocking fact was that the film was called as a bane to decency of India won several awards at national level for its direction, actress Seema's bold and flawless acting and best film of the year(in critics) after its release ,it also got a huge anticipation for its truthful and righteously contented story.Sometimes one can expect the unexpected and same happened here,being an 'A' rated movie it endorsed an impactful image in the Indian cinematography.This movie was considered radical by

"Evening standard".

It was precisely the flaw of the CBFC that threatened to stall the release of the The Bandit queen movie. Twenty-two years later, that flaw remains. Governmental interventions, as a result, have become more direct, prohibiting films from playing even at festivals. On the other hand, the number of audience members like Hoon has only increased, holding films hostage on the flimsy ground of hurt sentiments.

Many masterpiece artworks get curbed due to the scissors by the governmental agencies and laws giving an negative incentive to the women empowerment and many grieving issues of the society. The freedom of speech has limitations, but does, freedom include unreasonable limitations?

Nine Hours to Rama

In 1962, the Indian government banned the novel, Nine Hours to Rama by the historian Wolpert, an emeritus professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. It is a fictional account of the last day of Gandhi’s life, and focuses on the conspirators who plotted and carried out Gandhi’s assassination at a prayer meeting in 1948. It got banned because it exposed the poor security provided to Gandhi, and hinted at possible incompetence and collusion.

Based on Wolpert's novel, Nine Hours to Rama offers a lavish reconstruction. Mark Robson shot on location in India, with expansive crowd scenes, historical recreations and beautiful Panavision photography by Arthur Ibbetson. Robson intersperses thriller dynamics with flashbacks, signaled by Ernest Walter's nifty slow dissolves reminiscent of Orson Welles. Malcolm Arnold contributes an authentically Indian-inflected score, using sitar and percussion to create atmosphere.

Rama isn't strictly accurate: Godse's depicted as the son of a priest radicalized by his father's death, when he was a middle class fanatic who gradually soured on Gandhi. His romance with Rina provides a tasteful foil, casting Godse's reactionary radicalism against his lover's modern-thinking moderation. This only seems false at the end, where Godse wavers in his resolution to kill Gandhi if Rina will elope with him. This twist provides a contrived, though necessary jolt of suspense.

Thrillers based on real assassinations must avoid the shortcoming of inevitability. Rama is no Day of the Jackal; its killer isn't a remorseless professional but a bumbling activist who escapes through craftiness and dumb luck. Police arrest his compatriots, an argument with a hotel keeper nearly lands him in trouble. He hides with a prostitute (Diane Baker) who steals his gun, bluffs his way past an inquisitive cop and feuds with handlers who doubt his commitment. Through sheer determination (and Gandhi's fatalism), he narrowly keeps his date with destiny.

It's possible many viewers won't sympathize with Godse, anymore than they'd embrace a Lee Harvey Oswald or James Earl Ray biopic. No amount of tragic backstory will change that he murdered an admirable human being. Screenwriter Nelson Gidding's tries at framing a broader historical context are often murky and undercooked. That much of the cast are Caucasian actors in brownface presents another hurdle, though Robson's sober staging avoids caricature or overt offensiveness.

Still, Rama's suspense element is without fault. The cat-and-mouse drama works wonderfully, with Superintendent Das trying to reason with Gandhi as Godse dodges police and closes in. Robson mounts the finale with explosive skill, with Godse edging through a teeming crowd, struggling to maintain composure amidst deafening chants and swirling doubts. The ending is affecting for all its certainty.

Horst Buchholz is surprisingly good, playing Godse as hot-blooded and angry, channeling personal resentment into a greater cause. Jose Ferrer's Superintendent is a one-note foil. Brits Robert Morley and Harry Andrews are less convincing as other Indian officials. Valerie Gearon is compellingly tough-minded, Diane Baker fighting shame and bewilderment. J.S. Cashhyap is a dead ringer for Gandhi, making the most of limited screen time.

Whether through its alienating premise or awkward casting, Nine Hours to Rama fell through the cracks. Nonetheless, it holds its own against later, better-known assassination dramas.

-Ananya Saxena

The Satanic Verses

|

| The Satanic Verses |

India is the largest democracy known for its diversity. Predicted to bring problems, this nation has been able to prevail through its constitution which has guaranteed us all the freedom and rights. India has had its fair share of controversies in which one’s freedom was compromised upon by the state with a view to maintain peace and order in the country. A famous victim of this situation has been Salman Rushdie, the Booker Prize winning author of the famous novel Midnight’s Children. His other book The Satanic Verses was the victim of the above-mentioned situation for allegedly mocking Islam.

The Satanic Verses is partly inspired by Prophet Muhammed’s life and the early days of Islam. The title itself is inspired by a group of Quranic verses that refer to three Pagan Meccan Goddesses: Allat, Uzza, and Manat. These verses are themselves controversial for being revealed to Muhammed by the Satan instead of God and there is quite a debate over their authenticity.

The book consists of frame narrative interlaced with a series of sub-plots that are narrated as dream visions experienced by one of the protagonists. The story revolves around Gibreel Farishta, an Indian expatriate to England and a Bollywood star specializing in playing Indian deities, and Saladin Chamcha, a voiceover artist who is having crisis with his Indian identity.

The novel traces the journey of the two protagonists trying to piece together their respective lives after they were involved in a plane crash incident. In the aftermath of this incident, Farishta takes the personality of Archangel and Chamcha that of the devil. Both of their lives are marred by this mental illness with Chamcha trying to exact revenge from Farishta for having forsaken him after their common fall from the exploding plane. The protagonists in the end reconciled with each other and returned to India.

In between this main plot are the imbedded sub plots in the form of dream sequences, ascribed to the mind of Farishta. One of these sequences contains most of the elements that have been criticised as offensive to Muslims. It is a transformed re-narration of Muhammed’s life (called Mahound in the book) in Mecca (called Jahiliyyah). At its centre is the episode of the so called ‘satanic verses’, in which the prophet first proclaims a revelation in the favour of the old polytheistic deities, but later renounces this as an error induced by the Devil. There are two opponents of Mahound: a demonic heathen princess and an irreverent sceptic and satirical poet, Baal. When the prophet returns to the city triumphant, Baal goes into hiding in an underground brothel, where the prostitutes assume the identities of the Prophet’s wives.

It is the above sequence which ruffled some feathers of the Muslim Oligarchy. This rallied the Muslims against the author and the book, a Booker Prize finalist. The author has had threats and fatwas issued against him, most famously by the then Supreme Leader of Iran, Ruhollah Khomeini who made Salman Rushdie his political scapegoat as he had sensed he was dying and wanted to issue his last fatwa (testament) and paint a new monster for the Islamic world.

Playing into his hands, the Muslims who hadn’t even read the book started protesting and made numerous attempts to murder Rushdie which they were unsuccessful in. But some translators and publishers were not that lucky. Hitoshi Igarashi, the Japanese translator was stabbed to death and 35 people were massacred in Sivas, Turkey when a mob of fanatics set a hotel on fire.

To avoid all of this madness the Indian Government banned the book, thus putting a blot on the freedom of speech and expression. The Indian Government opted the safe way out, knowing that the authors would not go on a killing spree like fanatics. This incident remains a blot in the pages of history, as the Government had to compromise upon its fundamental principles to please fanatics.

A bounty of $2.8 million on Rushdie’s head till this day, is a sign that freedom of speech has a foggy future especially in the nations’ literary community.

Rtr. Tanish Dhami

Comments

Post a Comment